Should public bodies in Illinois, like cities and school districts

and sheriff’s departments, be allowed to hide information from Freedom

of Information requests by keeping them in databases? That question is

before the 104th Illinois General Assembly, thanks to a bill sponsored

by Donald P. DeWitte, elected state senator by the wise citizens of

Batavia and Elgin (motto: “The City In The Suburbs”; indeed), and

prompted in part by my friend Matt Chapman.

I play a very small part in this story, so I get to tell it.

Background

Illinois has an excellent,

toothy FOIA statute.

With very

few exceptions, any information collected by an Illinois public body

is public property. Anybody is entitled to ask for it. You can’t

generally be charged for asking. Public bodies can’t really limit the

number of requests you make. They get just 5 days to respond, with 5

additional extension days if requested in writing. Improper denials can

get you legal fee recovery if you sue over them, so there are lawyers

that will take these cases on contingency. It’s pretty neat!

I think people are too shy about making FOIA requests. It’s easier

than it looks! You just need to send an email to the public body you

want information from. Put “FOIA” in the subject line. By law, there’s

no more ceremony to it than that. And you’ll find that the people

responding to those emails are generally kind and happy to help.

The one big limitation of Illinois FOIA (with FOIA laws everywhere, really)

is that you can’t use them to compel public bodies to create new

records. Often, what you’ll be looking for is some kind of report about

some issue of public policy. If that exact report exists, you’re golden.

But if it doesn’t, you have to find and request the raw data for that

report, and you have to assemble it yourself. This limitation is about

to matter a lot.

To understand what’s happening in this story, I’m going to have to

explain a technical concept: the idea of a “database schema”. More and

more of the information tracked by public bodies now lives in databases,

rather than filing cabinets or shared drives. Databases are organized

according to schemas.

Think of a modern database as a huge Excel spreadsheet file, with

many dozens of tabs. Each tab has a name; under each of those tabs is a

separate spreadsheet. Each spreadsheet has a header row, labeling the

columns, like “price” and “quantity” and “name”. A database schema is

simply the names of all the tabs, and each of those header rows.

Congratulations! You now understand databases.

Matt Chapman vs. City of Chicago

My friend Matt is a self-styled “civic

hacker” and a national expert at performing data journalism with

large-scale FOIA requests. Matt’s love language is pushing FOIA statutes

to their limits, sniffing out buried data and bulk-extracting it with

clever requests.

A good example of the kind of stuff Matt does is this ProPublica

collaboration about how Chicago issues parking tickets. After Matt

was towed over a facially bogus ticket and successfully took the city to

court over it, he got curious about the patterns of towing for things

like compliance violations. As it turns out, parking tickets have pushed

thousands of Illinoisans into bankruptcy, and, once you get

your hands on the ticket data, it turns out there’s a very clear

pattern of majority-Black neighborhoods being systematically targeted

for higher enforcement.

In the course of this reporting work, Matt learned about a system

Chicago operates called CANVAS. CANVAS is the central repository for all

parking ticket data in the city. It’s a giant database, and Matt would

very much like to know what’s in it. So he filed a FOIA request for the

CANVAS database schema.

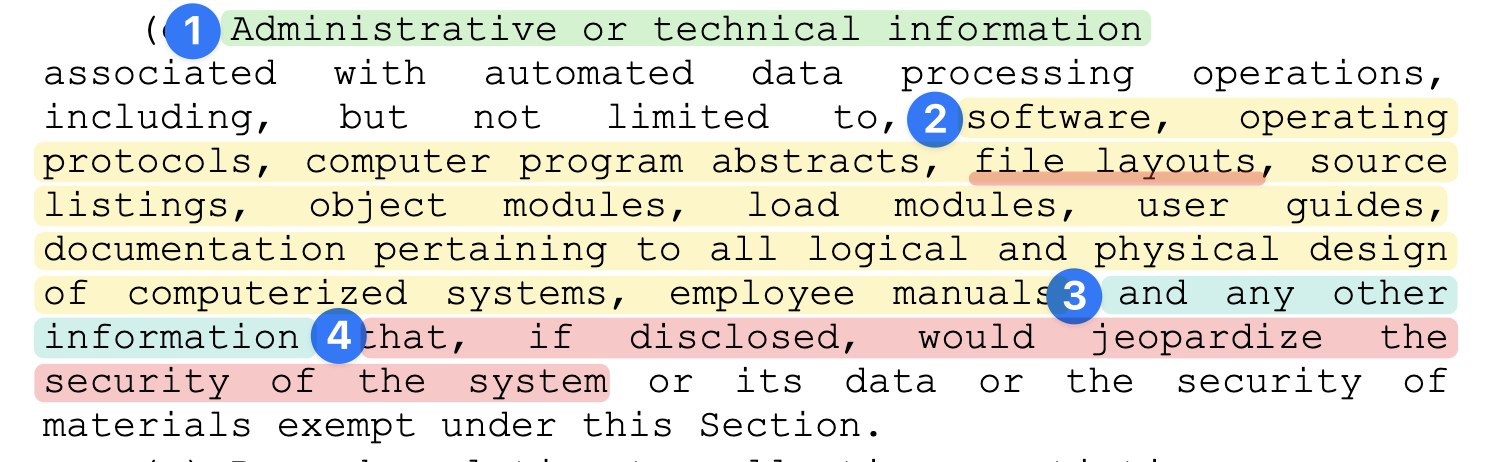

The city flatly refused. To do so, they relied on a specific

exemption in the statute:

“(o) Administrative or technical information associated with

automated data processing operations, including but not limited to

software, operating protocols, computer program abstracts, file layouts,

source listings, object modules, load modules, user guides,

documentation pertaining to all logical and physical design of

computerized systems, employee manuals, and any other information that,

if disclosed, would jeopardize the security of the system or its data or

the security of materials exempt under this Section.”

In plain English, this exemption says that public bodies aren’t

required to reveal information that might jeopardize the security of

their systems. You obviously can’t FOIA logins and passwords. You also

generally can’t FOIA the source code of programs they run. Chicago

claimed that Matt was a “hacker”, and that the CANVAS schema could in

the wrong hands put the city at risk.

With the help of Merrick Wayne and Matt Topic of Loevy and Loevy,

Matt sued the city. Here’s where I come in.

They Put Me On The Stand

Is the CANVAS schema too scary to give Matt Chapman? To decide that,

we have to answer a bunch of questions:

- Does disclosure of a database schema really jeopardize the security

of the system? - How plausible or likely does that jeopardy need to be?

- Does a database schema constitute “source code”?

- Is a SQL schema a “file format”?

- And, finally, does the “would jeopardize” language apply to

everything in the exemption, or just to the nearest noun “any other

information”?

I’ve spent the last 25 years of my life doing software vulnerability

research, which is a stuffy way of saying that I’m a software developer

who looks for bugs in software that would let people do scary things.

Matt retained me as his expert witness for his trial, which took place

in Cook County Chancery Court. Lined up against me was Bruce Coffing, the

Chief Information Security Officer of the City of Chicago.

The trial

would revolve mostly around questions 1-3.

At this point, I need to read you in to another technical concept:

“SQL Injection”. “SQL” is the language most programs use to talk to

databases. “SQL Injection” is a security vulnerability that programs

that use SQL can have. It’s the primary way databases get attacked, and it’s

straightforward to explain.

Applications that use databases include in their code “SQL queries”,

which are form-letter templates of questions they might need to ask the

database; for instance:

Retrieve the dates of every parking ticket issued to ‘[INSERT

NAME]’

Now, let’s say it comes time to pull tickets for “Dave Arnold”. Simple: stick

his name in the template:

Retrieve the dates of every parking ticket issued to ‘Dave

Arnold’

But now imagine we need to look up “Bob O’Connor”:

Retrieve the dates of every parking ticket issued to ‘Bob

O’Connor’

We’ve confused the database: the name in our query is surrounded by

quotes, but our name includes a quote. Normally, when your program has

this bug, it just generates an error message. But attackers look for

this bug, and do things like:

Retrieve the data of every parking ticket issued to ‘Bob O’ and also

all the rest of the information in the database including everyone’s

passwords.

This works because the quote the attacker supplied cuts off the text

placeholder in the template; all the rest of the attacker’s input gets

interpreted as code, which the database executes.

Most of the people who will read this post are annoyed with me for

taking the time to explain SQL injection. But that is the experience of

getting on the stand in Chancery Court and making an argument that the

CISO of Chicago was wrong about database vulnerabilities: trying to

ensure that a judge shares your understanding of how software

vulnerabilities work.

On the other hand, if you’re one of my non-nerd readers,

congratulations, you now know how to hack the Internets. If anybody

asks, I didn’t tell you any of this.

The bench trial for Matt’s case came down to the question of whether

releasing the CANVAS schema would enable this attack. Specifically,

Bruce Coffing argued:

- The schema makes it possible to spot

vulnerabilities. - Further, it makes it easier for attackers to be

sneaky about probing for vulnerabilities. - Finally, it helps attackers

pick which applications are most profitable to attack.

Coffing seems like a perfectly lovely and well-qualified person. But

no, no to all of this.

To Coffing’s first point: you don’t find SQL injection

vulnerabilities by reading database schemas. You find them instead in

the application’s source code, where those database template queries

live. Matt isn’t asking for source code. He just wants the header rows

from the tables.

Here I want to point out that I

fucked up in multiple ways expert-witnessing for Matt. For example,

in my affidavit, I wrote that SQL schemas would provide “only marginal

value” to an attacker. Big mistake. Chicago jumped on those words and

said “see, you yourself agree that a schema is of some value to an

attacker.” Of course, I don’t really believe that; “only marginal value”

is just self-important message-board hedging. I also claimed on the

stand that “only an incompetently built application” could be attacked

with nothing but it’s schema. Even I don’t know what I meant by

that.

I recovered my footing when I came up with this argument: “Attackers

like me use SQL injection attacks to recover SQL schemas. The schema is

the product of an attack, not one of its predicates”. This, too, is

self-important puffery. But I’ll tell you who loves “products” and

“predicates”, especially used in relation to each other in a single

sentence: a Chicago Chancery Court judge.

To Coffing’s second argument, about the schema helping attackers stay

off his radar when they try attacks, the problem is that every computer

system connected to the Internet is being attacked every minute of every

day. The noise is deafening.

Thousands of people have built scanner bot programs that probe every

computer system they can find and fire batteries of well-known attacks

(almost none of them ever work, but bots don’t get bored and give up,

and eventually the teenager in Malaysia who launched the bot gets

lucky). Chicago has no operational response to people turning the

doorknobs of their various applications. They can’t; if they did, they’d

spend all their time responding to kids in Kuala Lumpur goofing

around.

Finally, Coffing argued that having the schema might help an attacker

decide whether or not an attack would be profitable. A schema might tell

you, for instance, that an application deals in credit card data. The

thing is, CANVAS already tells you it’s dealing in sensitive

information: it’s the backend for processing parking tickets. You don’t

need a schema to know that CANVAS is interesting to attackers.

The judge bought my arguments. I think my attire gave me

salt-of-the-earth credibility; Coffing wore a suit.

Providing testimony was a lot of fun. I’d like to do it again

sometime. Litigation is super fascinating to watch! For example: we

wanted me to testify after Bruce Coffing, so we’d have some idea of what

arguments we needed to rebut. But we brought the FOIA case, so the

burden was ostensibly on us, and our witnesses went first. But, a-ha!

Invoking an exemption in Illinois FOIA is an affirmative defense, and

the burden of those arguments shifts to the defendant. But wait: to get

fee recovery under the law, we want to assert a willful violation of

FOIA; to make that claim, Chicago argues, the burden shifts back to us.

Ultimately, Matt Topic and Chicago compromised; Topic dropped

“wilfullness” and we got to go second.

I’m not saying this is the most interesting thing ever to have

happened, but only that if someone works out a way to use AI to make a

home version of Chancery Court trials that you can play on a

Playstation, I will rack up 10,000 hours playing that game easily.

We won. But Chicago immediately appealed. Matt Chapman didn’t get the

CANVAS schema. Two years later, the

case came before the First District Appellate Court.

The basic idea of the appeals court is that the original trial court

is the primary “trier of fact”. You appeal legal conclusions, but the

facts determined in the original case generally stand. Our bench trial

took care of questions 1 and 3. That left 2, 4, and 5. Here’s what the

appeals court found:

In considering the danger of disclosing information under FOIA,

how likely does an attack need to be?

Answer: it has to be very

likely.

The statute says “information that, if disclosed, would

jeopardize”.

Believe it or not, there’s case law on “would” versus

“could” with respect to safety. “Could” means you could imagine

something happening. But the legal standard for “would” is “clear

evidence of harm leaving no reasonable doubt to the judge”. The statute

set the bar for me very low and I managed to clear it.

Doesn’t this just

make you want to immediately drop everything and become a litigator? I

want to litigate!

Is a SQL schema a “file layout”?

If a schema isn’t source code and it isn’t a file layout, the exemption

doesn’t appear to apply at all. The verdict: “shrug emoji”. The appeals

court didn’t reach this question, because:

Does the “would jeopardize” language in the statute apply to

everything in the exemption, or just to the nearest noun “any other

information”?

Ladies and gentlemen it is time for some legal

mumbo-jumbo.

Here’s the FOIA exemption Chicago relies on:  To what does

To what does

the qualifying language at point (4) in this text refer? Is it “any

other information” (3)? Os is it “Administrative or technical

information”, meaning everything in the exemption?

If it’s the former, “any other information”, Matt has a problem. That

interpretation means things like file layouts (and

employee manuals and “load modules”, whatever those are) are per

se exempt; that the Illinois legislature meant them as examples of

things that would jeopardize security.

If it’s the latter, Matt has

already won: whether or not a SQL schema is a “software” or a “file

layout” or a “load module”, we’ve already proven that it won’t

jeopardize security.

The court decides it’s the latter. Also, that I am very charming. We

win on appeal. Chicago immediately appeals again. Whatever’s in CANVAS,

they really don’t want you and I to know about it.

A year and change later, the

case is decided before the Illinois Supreme Court. And, on the

question of how to read the FOIA statute, the Supreme Court disagrees

with the appeals court. The qualifying language in the statute applies

only to “any other information”. Everything else is “per se” exempt.

We started this legal process, of challenging Chicago’s attempt to

exempt CANVAS from FOIA, with 5 questions. What happens now is that the

4th question, of whether a schema is a “file layout”, finally becomes

very important. The Illinois Supremes have just decided that “file

layouts” are per se exempt under Illinois FOIA.

Is a SQL schema a file layout? Of course not. The same SQL schema can

be used by multiple database engines, and each will use a different

underlying file layout to manage the resulting data.

The McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Scientific & Technical Terms, 6E —

which the Illinois Supreme Court cites — describes a “file layout” as “A

description of the arrangement of the data in a file.” A SQL schema is

almost the exact opposite thing: it’s an abstraction of the data in a

file, invented specifically so you don’t have to think about how the

data is actually arranged. Checkmate!

Unfortunately, the Illinois Supreme Court had at their disposal a

second dictionary. In the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, a “schema”

is defined as “a structured framework or plan: outline”. “This is a

difference in name only”, said the court. Argh. Schemas are now file

layouts. We lose.

Where This Leaves Us

Obviously, we

should have won on appeal to the Illinois Supremes. If you sit on

that court, call me, we can straighten this out.

That said: today, Illinois public bodies can refuse to divulge

database schemas.

This is problematic, because more and more data is finding its way

out of file cabinets and shared drives and Word documents and into

specialized applications, where the only way to get at the underlying

data is to FOIA a database query.

Databases shouldn’t be a safe harbor for municipalities to conceal

information from the public.

But, thanks to the good people of Elgin, and also Crystal Lake

(motto: “No, Not The One From Friday the 13th”), the Illinois

legislature has an opportunity to fix this. SB0226

would add the following language to the statute:

[Public bodies] shall provide a sufficient description of the

structures of all databases under the control of the public body to

allow a requester to request the public body to perform specific

database queries.

⚡️Hell yes.⚡️

My understanding is that this bill was proposed in no small part

because Matt Chapman has steadfastly refused to shut up about this

issue, and so I’ll conclude this long piece by saying (1) obviously the

bill should pass, and (2) it should be called “The Chapman Act”.

Call your reps!